New Cochrane review finds promising evidence on the benefits of psychological therapy for aged care residents – one of Australia’s highest risk groups for depression

Celebrating a birthday on the ABC’s Old People’s Home for Four Year Olds

Article by Shauna Hurley

In 2019 the ABC’s Old people’s home for 4-year-olds captured the public imagination. Charting an intergenerational ‘social experiment’, the docuseries attracted more viewers than MasterChef, won an Emmy Award and inspired new intergenerational programs around Australia. For the first time, the lives of older people struggling with loneliness, isolation and depression in aged care were the subject of popular attention.

A year later, aged care was in the spotlight again for a very different and much more disturbing reason. The Australian Government’s Royal Commission into Aged Care handed down its findings on a national aged care system in crisis, characterised by widespread systemic failures, suffering, abuse and neglect.

While vastly different in scope and purpose, both the popular ABC program and the Commission’s painstaking documentation of historical and contemporary public policy failings underscored the urgent need for new approaches to residential aged care and individual needs. Perhaps nowhere more so than in the area of mental health.

Against this backdrop, a new Cochrane review on psychological therapies in residential aged care provides especially timely, relevant and useful evidence for policy makers, healthcare providers, older people and their families, friends and carers who want better quality of care and life for aged care residents.

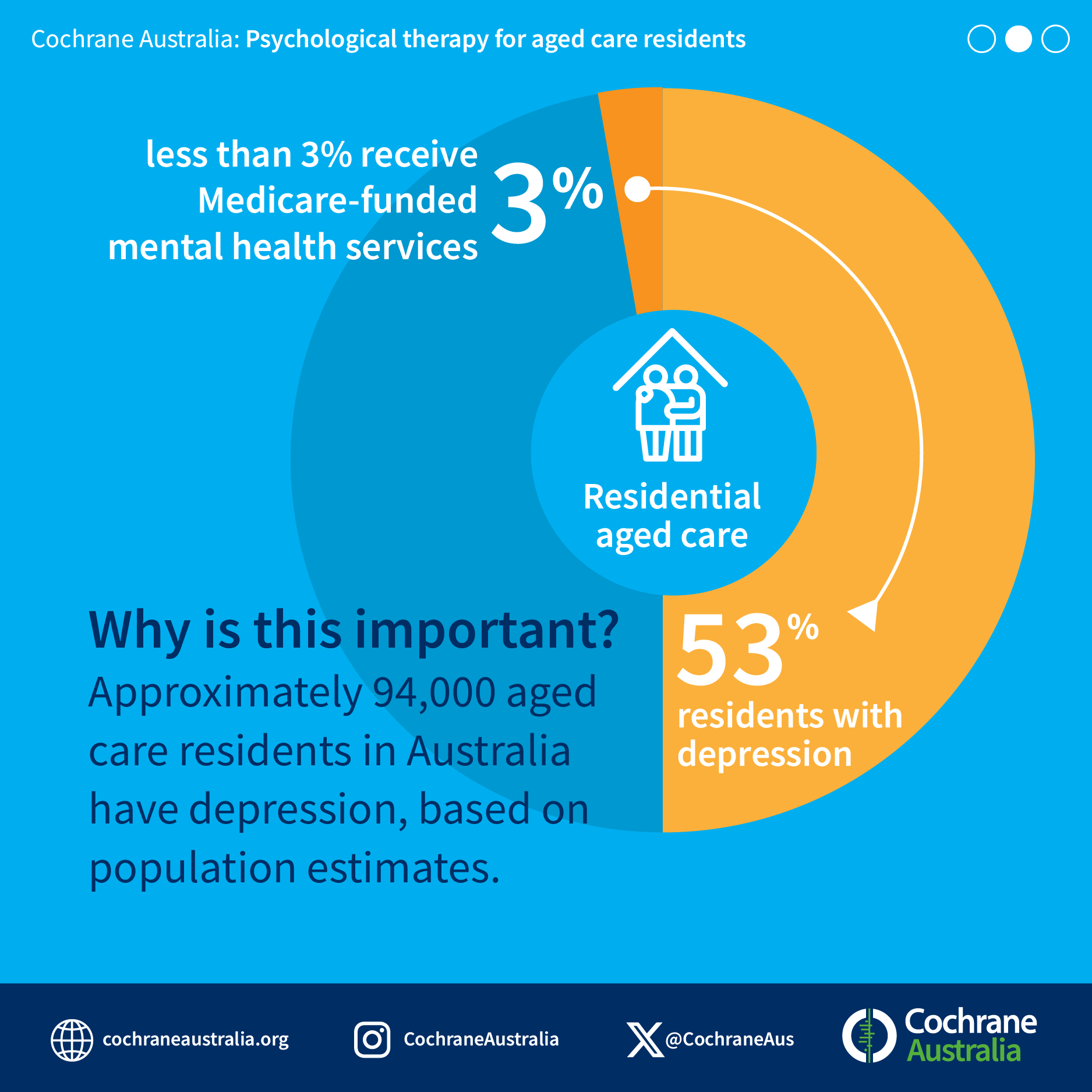

‘We wanted to take a much closer look at the potential for psychological therapies to help people with depression in residential aged care,’ review co-authors Professors Tanya Davison and Sunil Bhar explain. ‘We know aged care residents are one of the highest risk populations for depression. Data consistently shows that half of all Australian aged care residents experience depression, and concerningly those rates continue to rise. Until now, we’ve lacked essential information about the effectiveness of treatment approaches in the aged care setting.’

‘The good news is that our review found psychological therapy may be a suitable addition or alternative to the current approach, which is often characterised by an over-reliance on antidepressants. We know that around 33% of Australians aged 75-84 and 41% aged 85 and over were prescribed a mental health-related medication (typically an antidepressant) in 2020-21 – compared with 18% of the broader Australian population. We need to better understand why so many people are prescribed these medications in later life and consider potential alternatives.’

‘Psychological treatments like behavioural therapy, behavioural cognitive therapy and reminiscence therapy often seek to address the causes of distress. They can provide people with skills to help manage their symptoms and improve their daily lives. As such, we hope these latest findings can inform positive changes to the current model of care for depressed older Australians.’

Psychotherapy for aged care residents: what does the evidence tell us?

'Most older people treated for depression are prescribed antidepressant medications. However, researchers have noted that we lack robust evidence of their effectiveness for depressed aged care residents, and benefits appear questionable for the substantial proportion who are physically frail. To date, other treatment options like psychological therapies haven’t been widely available.’

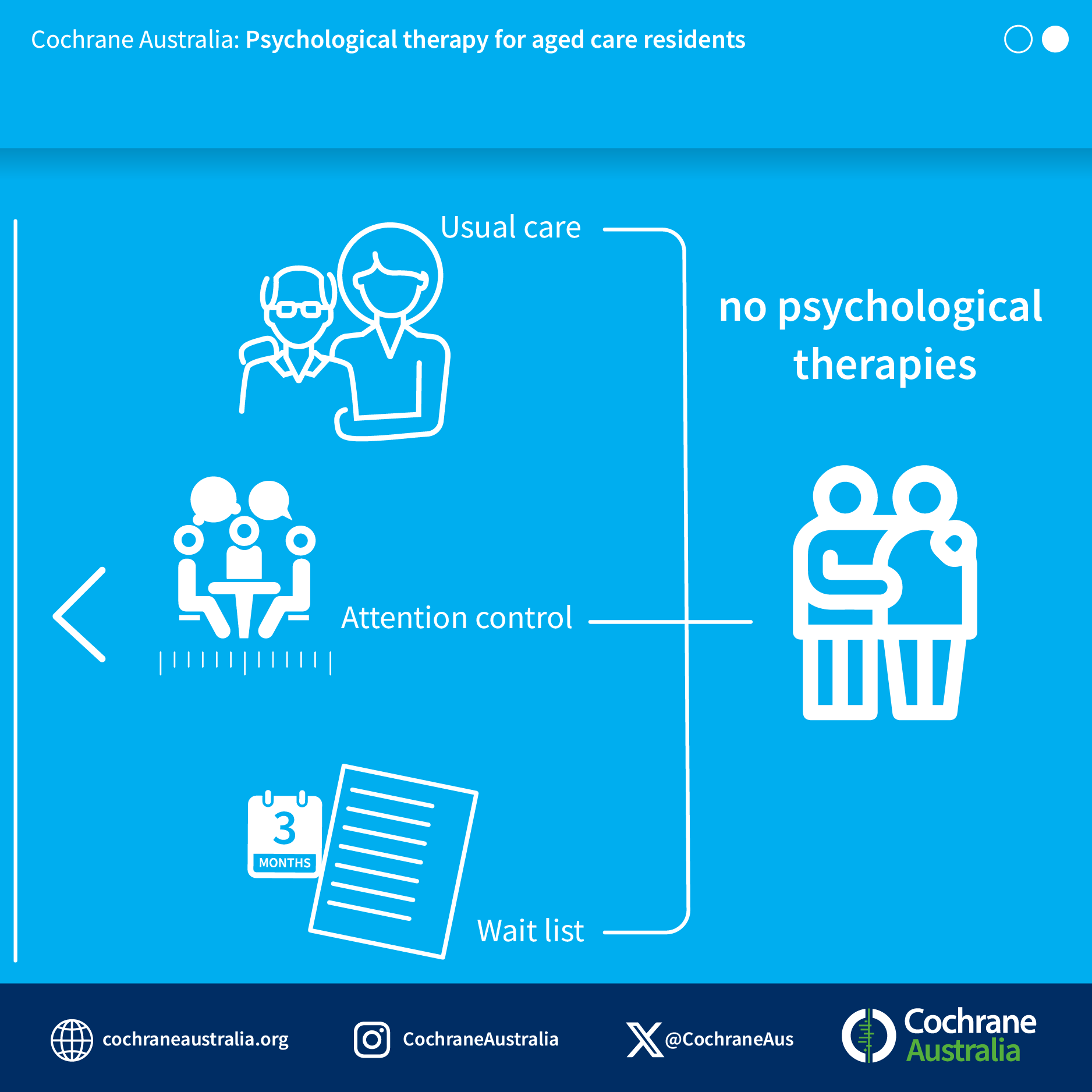

‘For our latest review, we evaluated clinical trials published around the world over the last 40 years that were designed to test the effectiveness of psychological treatments for depression in aged care residents,’ Sunil explains. ‘We looked at 19 trials from seven countries that involved 873 older people with significant symptoms of depression living in residential aged care facilities. Three different types of psychological therapies were tested – behaviour therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy, and reminiscence therapy.’

‘Our team found that psychological therapies may be effective in reducing symptoms of depression, compared with the usual approaches (such as antidepressants and access to activities within the facility) to caring for people, with effects lasting over several months. There’s also preliminary evidence suggesting psychological therapies may also improve residents’ quality of life and psychological well-being. Notably, most of these trials provided between just two and 12 psychotherapy sessions, which is promising from a feasibility and implementation perspective.

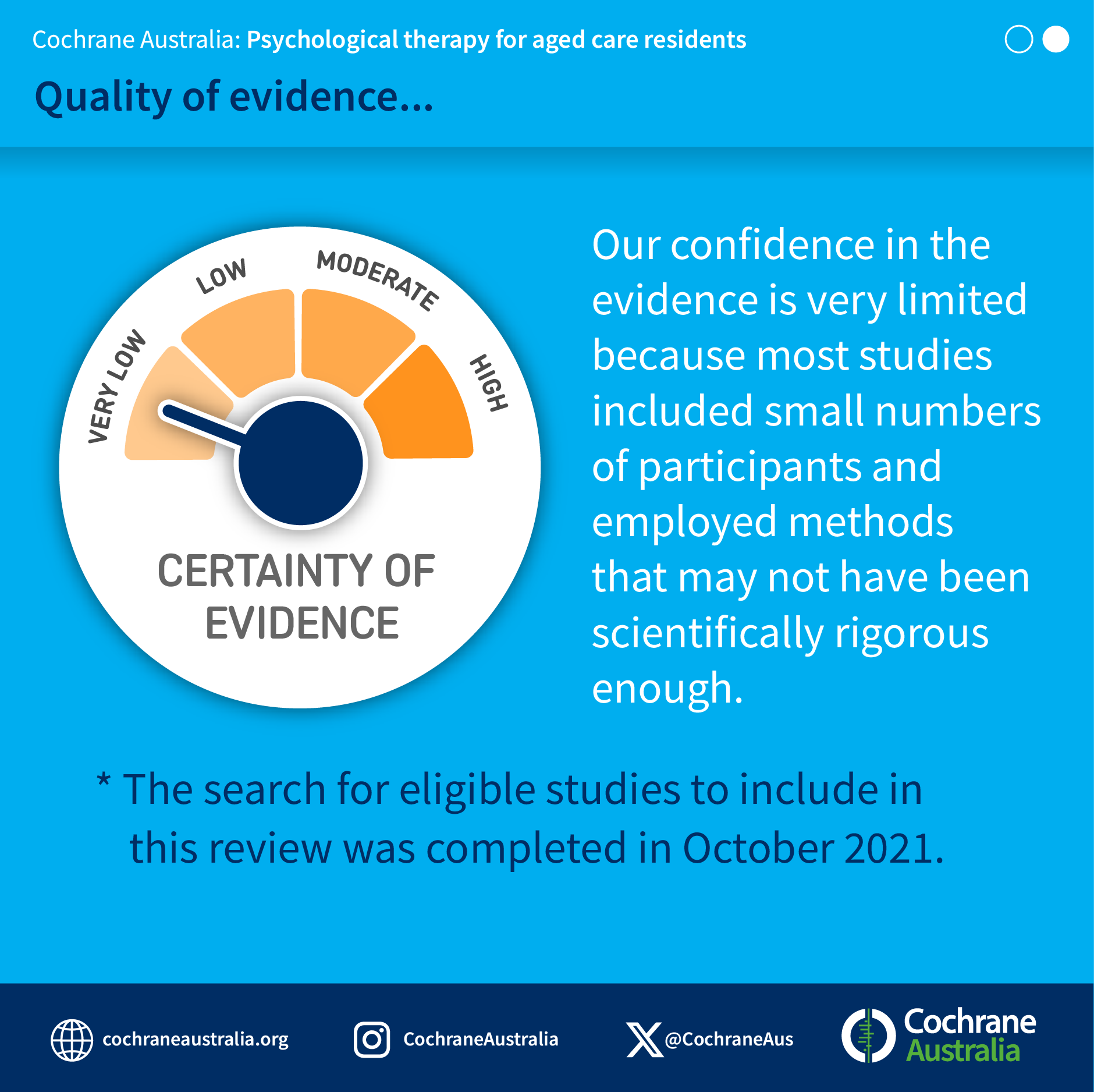

‘The main challenge in conducting this review was that some of the studies we looked at were quite poorly conducted,’ Tanya adds. ‘Ideally, we’d like to see more scientific rigour applied to this kind of research. However overall it was encouraging to see evidence that psychological treatments worked better than usual care in this very complex population across the studies we analysed.’

Looking ahead: challenges, questions and a call to action

‘Ultimately these findings serve as a call to action,’ Sunil says. ‘The question is how can we make these therapies available and accessible to all who could benefit from them. The focus needs to shift to implementation. For example, changing the culture of residential facilities to accommodate psychological therapies, training staff with the required competencies and bringing in therapies in a way that's affordable and accessible given significant funding restraints.’

‘Our review will no doubt spark debate over these and other complex questions, and I look forward to seeing how it might generate more creative research – not only in terms of the efficacy of treatments, but also in terms of the implementation of those treatments across residential care.’

‘Implementation and the need for higher quality effectiveness studies are certainly key,’ Tanya agrees. ‘Much more needs to be done to ensure older Australians – regardless of where they live – have equitable access to high quality mental health care. It’s important for everyone to understand that depression isn’t an inevitable consequence of moving into residential care. Many older people can and do adjust well. For those who don’t, there are different approaches to improving their mental health and quality of life. Psychotherapy is one such tool that could be offered routinely to those who need it, rather than relying solely on antidepressants.’

We need to add to this evidence base and keep aged care in the public spotlight to ensure real, practical change,’ Tanya and Sunil conclude. ‘Because as the Royal Commission and the experiences of older Australians in care clearly show, we have a such a long way to go. We hope our latest findings will contribute to much-needed change and improvements in residential care around Australia, now and into the future.’

Download the review infographic